Before now, I truly believed that any pretentious movie list of the decade had to include The Tree of Life, Terrence Malick’s commitment to unrestrained boredom.

I stand corrected.

Below me sits the work, in –yikes- 2,260 painful words, of New Yorker film critic Richard Brody. Not to pick on Richard specifically –there are a ton of pretentious movie critics- but Richard Brody offered up his list of the 27 best movies of the decade … and it’s the worst list I have ever seen … of anything. It’s worse than Santa’s naughty list or Nixon’s enemies list.

Here is the article in its entirety. I didn’t want Richard to feel I was slighting him or putting words in his mouth. But do feel free to ignore his long-winded thesis on how Hollywood has destroyed the industry and skip straight to the films and why I think his list is full of crap.

The Twenty-Seven Best Movies of the Decade

By Richard Brody

New Yorker Magazine

November 26, 2019

From an artistic perspective, the past decade in movies is the decade of mumblecore. The movement of intimately scaled, often improvised, low-budget dramas and comedies that pull their actors from the lives and milieux of filmmakers who build stories around their personal experiences has become the energy-giving core of the American cinema. All decade long, aside from the reliably surprising masterworks by established filmmakers such as Martin Scorsese, Clint Eastwood, Spike Lee, Sofia Coppola, Wes Anderson, Jim Jarmusch, Frederick Wiseman, and Paul Thomas Anderson, there has been a profusion of daring films by younger filmmakers who are part of the mumblecore constellation, as well as a bunch of actors (and cinematographers and other artists) who emerged from those films.The mumblecore generation has now entered, and in many ways transformed, the true mainstream of movies: Greta Gerwig, Terence Nance, Josephine Decker, Andrew Bujalski, Amy Seimetz, Barry Jenkins, Joe Swanberg, Lena Dunham, Adam Driver, Sophia Takal, Nathan Silver, Shane Carruth, David Lowery, Kate Lyn Sheil, Alex Ross Perry, Kentucker Audley, Lynn Shelton, Robert Greene, Ronald Bronstein, and the Safdie brothers, to name just a few. I could nearly have filled my decade list with their films—but, in the interest of spreading (and acknowledging) the love, I included only a few exemplary ones.

Of course, what’s overarchingly important in this decade in movies reaches far beyond the movies themselves. Most crucially, this has been the decade of the public acknowledgment—with the activism and advocacy of the #MeToo, Time’s Up, Black Lives Matter, and #OscarsSoWhite movements, along with the accusations against Harvey Weinstein and many other men in the media—of the rotting foundation on which the film industry and society at large are built. The misrepresentations, whitewashings, banalizations, and exclusions that have sustained the Hollywood system have begun to come to light, and there have even been consequences for some of the perpetrators.

The response of the movie industry to this heroic and pain-filled activism has been not even quarter-assed. The Academy has taken much bruited yet minor steps to diversify its membership (which still named the white-savior movie “Green Book” Best Picture). Reboots of mediocre so-called classics get made with women in the leading roles and, often under men’s direction and studio supervision, improve the rancid source material incrementally. Superhero productions feature three women striding silently into battle rather than none, and reliably include actors of color in roles of ahistorical and impersonal substance. There are the noteworthy exceptions, such as “Black Panther,” which, as good as it is, remains the one film that the system’s defenders trot out as its justification.

Yet this decade has also seen, in surprising ways, the convergence of these two currents of activism and aesthetics in ways that I hope will continue in the next decade and beyond. Many of the substantial changes in the industry have come from the new generation of filmmakers—yes, mumblecore. Its creators put into bold artistic action the fundamental premise that promises to turn minor shifts in the industry into a sea change: namely, the idea that the personal experience of filmmakers and a film’s participants is inseparable from the film’s process, its subject, its contents, and its style. (The idea is at work in documentaries, too.) The necessity, the urgency, of diversifying the ranks of directors is inseparable from the diversification of the spectrum of experience—and of artistic inspiration—that the cinema can offer. The first-person accounts, the daringly original artistry, and the self-aware and group-oriented activities of these filmmakers have opened the cinema to far more varied voices and ideas.

The rise of this generation of filmmakers has coincided with the rise of independent production, which has taken the place of studios for director-driven movies. At the same time, this shift hasn’t helped many independent filmmakers from earlier years whose artistry is among the treasures of their times and whom the industry has nonetheless ignored. This decade was also the decade in which Julie Dash, Wendell B. Harris, Jr., Rachel Amodeo, Leslie Harris, Zeinabu irene Davis, and Billy Woodberry still didn’t make their second features. Spike Lee long found himself shut out even of independent financing, using his own money for “Red Hook Summer” and then turning to Kickstarter before being, um, reëstablished, at a time when he was already long established and his projects should have been prime productions.

Nonetheless, independent productions, including both new filmmakers and the generations of veterans, have, for the most part, proved to be liberating for filmmakers, and that system is one of the reasons why American filmmaking has been so artistically innovative all decade long—even if much of that filmmaking has been an economic sidebar to Hollywood product.

The decade of independent filmmaking not coincidentally parallels the decade of the Marvel juggernaut, which began in 2008, with “Iron Man,” and soon thereafter came to dominate the box office, the release calendar, and multiplex screens—three factors that are askew to the art of movies. What renders the Marvel trend significant is that it has come to command the so-called discourse and has marked the careers of directors and actors. Superhero movies themselves may offer a modicum of pleasure, and, on rare occasion, even more. Some of them feature delightful effects, moments of symbolic resonance, playful humor, and even a few striking performances that mesh well with the stark (or, rather, Stark) writing. These pleasures—yes, authentically cinematic—are, however, secondary to the over-all tone that these movies convey: highly managed production to the point of inhumanity. The superhero movies seldom transmit more than a glimmer of personal sensibility, and almost never do so through the essence of movies: images and sounds. The green screen and the computer graphics take precedence. That’s why many directors of less-than-distinctive visual sensibility get hired by Marvel to make superhero movies; they basically direct actors, while the “visuals” are farmed out to technicians and specialists. That’s also why the Marvel movies are, over all, deadening.

Many critics bemoan another of the decade’s trends, a related one: because the studios have turned to superheroes, children’s movies, franchises, and assorted other bombastic spectacles, they’ve stopped making (or, actually, drastically cut back on) so-called mid-range dramas for adults. I find the complaint misplaced: there are plenty of good and substantial movies being made, not often by the studios but, rather, by independent producers, and also by streaming services. Meanwhile, that category’s place in the mainstream has been taken over by serious-minded television series—and, with only a handful of exceptions, they’re basically the same thing: script-delivery systems, minus discernible directorial originality or inventiveness. When studios were the only game in town, directors went to them hat in hand, knowing that, with large budgets at stake, their films had to be commercial. Most of the best ones weren’t (one timely example: Martin Scorsese’s “The King of Comedy,” from 1983, cost nineteen million dollars to make and took in two and a half million dollars at the box office), and, as a result, the best directors’ careers were imperilled, often stalled, even completely shut down.

Now such ambitious movies of substance are rarely being made by studios but by independent producers, and they’re not being made on a mid-range budget but on low budgets. In exchange, directors are freer than ever to make movies without the distortions and the trivializations that the heavy hands of studio executives imposed. Filmmakers themselves, and their personal visions, are what’s being sold by these independent producers, and, as a result, they can make movies as they see fit—which is why there are many more American movies on the decade list than I expected going into it.

At the same time, while directors are freer to be themselves, so are the studios. With franchises and superheroes, they’ve become the brazen cash machines that they’d always been suspected of being, and that the occasional work of great high-budget art belied. The studios have unmasked themselves, in an eerie but apt parallel to the national political unmasking that has occurred in this decade. Just as the Republican Party has, in the age of Donald Trump, been liberated to be openly what it has been functioning as for the past half-century—a white people’s party—so Hollywood has been liberated by superhero and franchise fandom from the effort to make dignifying and self-justifying productions, and the studios are, for the most part, pursuing their commercialism and peddling their illusions unabashed. What’s more, the Trump Administration is making a similarly brazen effort to boost the studios and crush the opposition of independent producers and exhibitors, by moving to overturn the crucial antitrust ruling of 1948, which led to the rise of independent producers and exhibitors (and a vast outpouring of creative filmmaking) at that time. We’ll be back to discuss the results of this chicanery ten years from now.

The place of politics in the making and releasing of Hollywood movies is trivial, however, compared to persecution occurring elsewhere, including the arrest and imprisonment of filmmakers in Iran and Russia, and China’s repression and elimination of its formerly thriving and vital independent film scene. As Rebecca Davis recently reported, in Variety, what promises to follow in China are “independent-style films that look and feel like indies—yet are nonetheless studio-financed and exist within China’s strict censorship regime.” The rise of movie theatres—and the importing of Hollywood movies—in China, and the counterpart of the investment by Chinese producers in Hollywood, promises yet another dire shift. Not only are Chinese filmmakers unable to make frank movies about Chinese society, but American studios are equally disinclined to run the risk of displeasing Chinese authorities (and no movie is shown there without government permission). The Tiananmen Square massacre and China’s current genocidal policies toward the Uighur population won’t show up in any Hollywood film soon—and neither, I suspect, will Richard Gere, whose support for Tibetan cultural freedom has virtually got him blacklisted.

If Hollywood studios no longer seek the cover of dignity that comes with making and releasing individualistic movies of doubtless lower profit, the executives in charge don’t seem to really care. It’s now the prominent streaming services, principally Netflix and Amazon Prime—the main competitors to theatrical distribution—that seek to prove themselves as more than mere disrupters of the cinematic economy but, rather, as positive contributors to the cinematic ecology. To do so they’ve been producing, acquiring, and releasing exceptional movies that the studios wouldn’t and that other independents couldn’t, such as “The Irishman,” “Marriage Story,” “Chi-Raq,” “Paterson,” “Atlantics,” and “Manchester by the Sea.” Many of the best new movies are being produced or released by streaming services, which is to say that they’re more widely available, albeit for home viewing, than independent or international films ever were in times centered on theatrical distribution—yet few of them get the attention they deserve, simply because they often fly beneath the radar of publicity.

That’s where critics come in. The decade’s notable democratization and diversification of criticism that has resulted from online publication and social media has introduced writers who—by taste, enthusiasm, and knowledge—are inclined to call appreciative and discerning attention to such films. Yet online activity has also led, both maliciously and inadvertently, to versions of the pile-on, which have affected coverage of movies. The malicious kind is all too obvious: fanboys who, when the nakedness of their emperor (whether superheroic or political) is stated, react with rage ranging from insults to ethnic slurs to rape threats and death threats. (Needless to say, such hostility serves to make critics hesitate to express themselves freely, and it disproportionately targets female writers and writers of color.)

The other, inadvertent kind of pile-on is a perverse by-product of popularity: not only do a small number of blockbuster movies dominate the industry’s economy, but the sheer fact of popularity (and the related phenomenon of celebrity) is multiplied and amplified online. As a result, editors seek more and more coverage of those megaphenomena, crowding out coverage of less-popular yet ultimately more significant movies—at precisely the moment when, because these movies get scant distribution and are often virtually hidden on streaming sites, critical attention is all the more essential to their recognition. Criticism on the Internet increasingly replicates the polarization of filmmaking and distribution: the discussion agglomerates around a small number of films that will likely prove trivial in the history of cinema while overshadowing, in their time, the movies that will endure.

That’s where this list comes in. It would have been both boring and inaccurate to cull the movies from the top of my annual lists from the past decade. In reconsidering the decade’s films, I found that some of my own priorities and passions shifted, in two opposite directions: toward the unique sense of experience that filmmakers avow and forge, and toward the sense of originality, of reconsidering and reconfiguring the nature of cinema as such. Also, I found that there are filmmakers who are as great and as important as any represented on this list, but whose over-all body of work takes precedence over any individual film (for starters, Terrence Malick, Hong Sang-soo, Ava DuVernay, Joe Swanberg, Robert Greene, James Gray, and the late Chantal Akerman and Agnès Varda). Twenty-seven films—I couldn’t cut further—in numerical order (though, except for the first few, that order only holds approximately, and its specifics reflect specific inclinations at the moment I hit “send”). By design, only one film on the list is from 2019; I’ll have more to say about this year soon.

“The Wolf of Wall Street” (2013), Martin Scorsese

“Madeline’s Madeline” (2018), Josephine Decker

“Get Out” (2017), Jordan Peele

“An Elephant Sitting Still” (2019), Hu Bo

“Did You Wonder Who Fired the Gun?” (2018), Travis Wilkerson

“The Future” (2011), Miranda July

“Margaret” (2011), Kenneth Lonergan

“The Grand Budapest Hotel” (2014), Wes Anderson

“Somewhere” (2010), Sofia Coppola

“Li’l Quinquin” (2015), Bruno Dumont

“Film Socialisme” (2011), Jean-Luc Godard

“An Oversimplification of Her Beauty” (2013), Terence Nance

“Holy Motors” (2012), Leos Carax

“Coma” (2016), Sara Fattahi

“Red Hook Summer” (2012), Spike Lee

“Zama” (2018), Lucrecia Martel

“Moonlight” (2016), Barry Jenkins

“The Mule” (2018), Clint Eastwood

“It Felt Like Love” (2014), Eliza Hittman

“The Last of the Unjust” (2014), Claude Lanzmann

“In Jackson Heights” (2015), Frederick Wiseman

“A Ghost Story” (2017), David Lowery

“A Screaming Man” (2011), Mahamat-Saleh Haroun

“A Quiet Passion” (2017), Terence Davies

“Taxi” (2015), Jafar Panahi

“Let the Sunshine In” (2018), Claire Denis

“Infinite Football” (2018), Corneliu Porumboiu

An open letter to Richard Brody:

Good Lord, man. Are you being paid by the word? How could you talk for that long and have nothing to say about the actual films? I mean, that’s what we want to know. That’s what I want to know – how do you justify your inclusions other than your blanket thesis “they weren’t Hollywood?”

I find this list so offensive that it gives a bad name to critique.

Where to begin? How about some statistics:

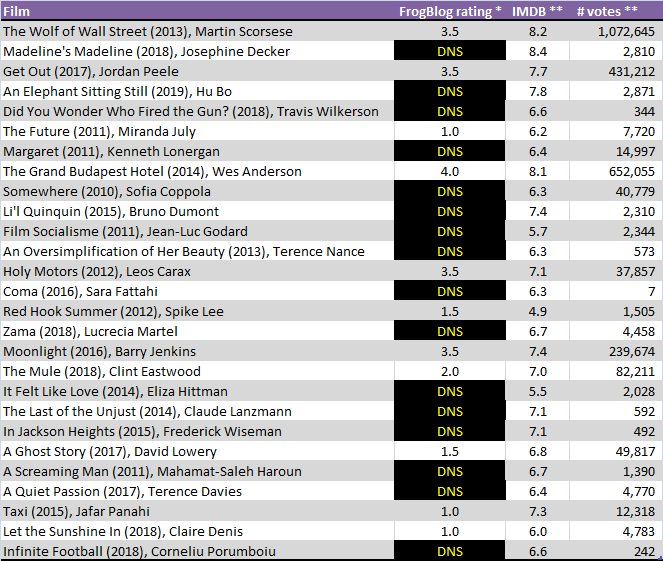

- 27 films

- Imdb average: 6.8 as of this writing

- Average # of imdb votes: 99,000 as of this writing

- Average # of imdb votes if you take out The Wolf of Wall Street, Get Out, The Grand Budapest Hotel, Moonlight, and The Mule (i.e. the films an average film-goer might know): 8,864

- Current # of votes for Coma (2016): 7

- Current Imdb rating for Spike Lee’s Red Hook Summer: 4.9 (on the list)

- Current Imdb rating for Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman: 7.5 (not on the list)

- # of films on the list I’ve seen: 11 (out of 27) Yes, this pisses me off and I will get into it

- Average rating I gave to the 11 films I’ve seen: 2.36 (out of 4)

- Number of films that I saw and panned: 5 (The Future, Red Hook Summer, A Ghost Story, Taxi, Let the Sunshine In … and I wasn’t exactly kind to The Mule, either)

First, the obvious. “27” is a fairly odd number. 27 says, “There were exactly twenty-seven awesome films this decade, not one film more. Not one film less.” Do you see how pretentious that sounds right from the get-go? I mean especially since the only huge film on the list is a Martin Scorsese (gee, big stretch for a New Yorker, pal) and you’ve also included a Spike Lee film that objectively might not make Spike Lee’s own top five for the decade. You clearly didn’t care about article length, so this is a definitive list. Do you see how douche-y this all sounds already before I even get into some of the crapshoot inclusions?

I would bet a lot of money that the only person to have seen every one of these films is Richard Brody. That’s not a big stretch. The number of people in the world who have actually seen Coma is most likely under 5,000. One film and I’m already at a minuscule subset. And there are ten other completely bizarre titles on the list.

I’ve seen over 2,200 movies in this decade. I would also bet heavily (I don’t know this for a fact, but I would bet) that you, Richard Brody, have not seen 2,200 films this decade. This doesn’t make me better than you; it’s not who saw the most films. But here’s the thing – you can’t make a list of films you haven’t seen. And as you have such a clear and naked disdain for major studio film that I’m guessing you rarely see any. To which I say, truly, how do you know it’s all bad? And for somebody with such an eclectic group, there are not a whole lot of  Asian films on the list, either, pal. I feel like you drew this list entirely from ten stints at Tribeca. And I bet I’m not far off.

Asian films on the list, either, pal. I feel like you drew this list entirely from ten stints at Tribeca. And I bet I’m not far off.

Now, imdb –as I’ve said many times in the past- is not necessarily an indicator of quality. But I think we’re allowed to make some inferences, especially as only the Clint Eastwood film and the Spike Lee film were likely to draw imdb ballot humping among the usual idiots. The average rating for these films is 6.8. Know what kind of films rate 6.8 on imdb? Sleepless in Seattle, Tron, Clueless, Heaven’s Gate, Pretty in Pink. Some of those are decent films and Heaven’s Gate was considered the biggest disaster of the 1980s. All the same, I don’t think people are going to to bat for Tron or Clueless as the “best film I’ve ever seen.” I deliberately chose pre-internet films. i.e. films that did not have the benefit of current media explosion. Sleepless in Seattle by itself has as many votes as 21 films on your list combined.

So lemme sum this up in case you’re not following: Nobody saw these films but you, and those who did weren’t floored by them. Do you have any idea how arrogant that sounds?

I saw 11 films on the list. Eleven. I average over 225 films a year. I consume films like children consume Cap’n Crunch. I see a year in film as “I’m Pac-Man and I have to clear the board.” And yet somehow I’ve managed to miss 60% of the best films this decade?! Well, gosh, Mr. Brody, how can I be as enlightened as you? Damn right I’m pissed off. I read film lists like this to figure out what I’ve missed (if anything) or to get a good sense of the critic. Your list gives me nothing but a message of: “I’m a pretentious jerk.”

My personal favorite subsection of this list are your 2018 inclusions. You list six 2018 films: Madeline’s Madeline, Do You Wonder Who Fired the Gun?, Zama, The Mule, Let the Sunshine In, and Infinite Football. I saw 275 films in a theater last year. Two-hundred and seventy-five theater films. That doesn’t even count Netflix and Amazon Prime additions. Does that sound like a low total to you? I saw every.single.film nominated for any Oscar –save two documentaries- and that includes the foreign and minor nominations. And yet I missed four of the six best for the year, is that correct? The two I saw? The Mule and Let the Sunshine In … I will quite happily never see them again.

So let’s assume I’m not an authority. And perhaps imdb is a poor judge. And perhaps studios constantly prefer mediocrity they can sell instead of  quality art. And perhaps people who vote for Oscars are all morons. And perhaps people who spread word of mouth don’t know what they’re talking about. And perhaps other critics themselves are also morons. Heck, I’ve said as much on several occasions.

quality art. And perhaps people who vote for Oscars are all morons. And perhaps people who spread word of mouth don’t know what they’re talking about. And perhaps other critics themselves are also morons. Heck, I’ve said as much on several occasions.

But, and I mean this as in: I’d like you to answer … but Richard, who is left? This list literally insults everybody. It says, “Only I know what a quality film is. Every.single.other.person who works in movies, votes for movies, writes about movies, or even watches movies is a complete moron.”

Would a list of 27 random films that occurred in the last decade be any worse? Could a list of 27 random films in the last decade be any worse? If I’m being honest, you don’t get Wolf of Wall Street, Budapest Hotel, or Get Out by accident, but take away those three, and I would literally choose a random selection for the remaining 24 over this one. I’m not kidding.

I don’t expect people to read my words. I’m not in it for the money or the fame. I write about film so that I leave a small legacy to show how I enjoyed some of my time on the planet. That’s good enough for me. But, dammit. After reading your words, Richard Brody, I think I ought to be given a shot at major publication; your readers cannot possibly do any worse.

BTW, my “Best of the Decade” list … it’s coming out after my yearly lists. It will almost certainly be a collection parsed from my yearly best lists because I’m not a sociopath. Doesn’t that make more sense? A lot more sense?

* DNS = Did not see

** Figures accurate as of 12/1/2019